28. Developing your own agents

By now, you should be very familiar with the concept of agents. You have interacted with them via commands and messages throughout this handbook, but what exactly is an agent?

If you lookup the Wikipedia entry for a software agent, you’ll find:

The term agent describes a software abstraction, an idea, or a concept, similar to object-oriented programming terms such as methods, functions, and objects. The concept of an agent provides a convenient and powerful way to describe a complex software entity that is capable of acting with a certain degree of autonomy in order to accomplish tasks on behalf of its host. But unlike objects, which are defined in terms of methods and attributes, an agent is defined in terms of its behavior.

retrieved 8 September 2019

In this chapter, we take this somewhat abstract concept and crystallize it by developing a simple agent. While the idea of writing your own agent might sound daunting at first, you’ll soon see that it is actually quite easy!

28.1. Unet agents

Agents are the basic building blocks of the UnetStack. They exchange messages, provide services and implement protocols. While what is expected from a well-behaved agent is quite demanding, most of the necessary core behaviors are already implemented for you by the

UnetAgent

base class. All you need to do is to extend it, and add in a little code to teach the agent what you want it to do.

| While you have the option of writing agents in Java or Groovy (or any other language running on the Java VM), we recommend writing agents in Groovy, as Groovy agents tend to need less biolerplate code and are more readable and maintainable. They are also easier to test as Groovy classes can be dynamically loaded from source, without having to pre-compile them. However, if you are already an expert in Java and prefer to use it, you’re welcome to do so. |

The basic skeleton of a Groovy agent looks like this:

import org.arl.fjage.*

import org.arl.unet.*

class MyAgent extends UnetAgent {

@Override

void setup() {

// this method is called when the stack is initialized

// register services and capabilities that you provide here

}

@Override

void startup() {

// this method is called just after the stack is running

// look up other agents and services here, as needed

// subscribe to topics of interest to get notifications

}

@Override

Message processRequest(Message msg) {

// process requests supported by the agent, and return responses

// if request is not processed, return null

return null

}

@Override

void processMessage(Message msg) {

// process other messages, such as notifications here

// if a message is not interesting, it can be safely just ignored

}

}

While you don’t strictly need the

@Override

annotations, it is a good practice to use them whenever you are overriding a method from a superclass. The annotation tells the compiler that this is what you intend, and so if you make a typographical mistake and type in a wrong method name (one that doesn’t exist in the superclass), the compiler will warn you.

If you do not need any of these methods, you can skip the definition as the base class provides default implementations. There are a several other methods that you can override to customize your agent, but these are less commonly needed and so we’ll skip them for now. You’ll come across them later.

If you happen to be already familiar with the

fjåge agent lifecycle

, you may wish to note that the

setup()

method is called from the

init()

method of the agent. The

startup()

method is called from a one-shot behavior scheduled during initialization. The

processRequest()

and

processMessage()

methods are called from a message behavior added during initialization.

|

28.2. Groovy echo daemon

It’s best to illustrate with a simple example.

Let’s develop an

echo daemon

that will respond to each incoming

echo request

datagram with an

echo response

datagram containing the same data as the echo-request. We need a way to identify which datagram is an echo request, as we don’t want to be echoing datagrams intended for other agents or for the user. We do this by defining an echo request datagram as any datagram with protocol

USER

(recall that protocol numbers from

USER

onwards are available for your own applications to use). We do not want the response to use the same protocol, otherwise our daemon (running on the source node) could get confused and echo the response, which would in turn be echoed again by the destination node’s daemon, ad infinitum. So we use protocol

DATA

for the echo response datagram, as this protocol is intended for generic application data.

Here’s our daemon:

import org.arl.fjage.*

import org.arl.unet.*

class EchoDaemon extends UnetAgent {

@Override

void startup() {

// subscribe to all agents that provide the datagram service

subscribeForService(Services.DATAGRAM)

}

@Override

void processMessage(Message msg) {

if (msg instanceof DatagramNtf && msg.protocol == Protocol.USER) {

// respond to protocol USER datagram with protocol DATA datagram

send new DatagramReq(

recipient: msg.sender,

to: msg.from,

protocol: Protocol.DATA,

data: msg.data

)

}

}

}Let’s walk through the above code:

-

Our agent does not provide any formal services or capabilities, so we we skip the

setup()andprocessRequest()methods from the skeleton. -

The

startup()method looks up all agents providing the DATAGRAM service, and subscribes to any notifications from any of these agents. These notifications will inlcude theDatagramNtfmessages that are published when datagrams are received from another node. When a notification arrives, theprocessMessage()method will be called. -

In the

processMessage()method, we check for datagram notifications with protocolUSER, and respond to each of them by sending aDatagramReqto the sender of the notification, requesting it to send a datagram with protocolDATAto the node that sent the echo request, with the data copied from the echo request.

That’s it!

Do not get confused between

sender

and

from

, and

recipient

and

to

fields in datagram messages. The

sender

and

recipient

always

refer to the agents that generate and consume the message, respectively. These are entities within a single Unet node. The

from

and

to

are node addresses that tell us which node is transmitting the datagram, and which node is the intended destination.

|

It’s time for us to test this agent. Create a file called

EchoDaemon.groovy

in the

classes

folder and copy the above daemon code into it.

Now start the 2-node network simulation that we have been using as a testbed, and on node B, load the agent:

> container.add 'echo', new EchoDaemon(); (1)

> ps

statemanager: org.arl.unet.state.StateManager - IDLE

remote: org.arl.unet.remote.RemoteControl - IDLE

rdp: org.arl.unet.net.RouteDiscoveryProtocol - IDLE

ranging: org.arl.unet.phy.Ranging - IDLE

uwlink: org.arl.unet.link.ECLink - IDLE

node: org.arl.unet.nodeinfo.NodeInfo - IDLE

websh: org.arl.fjage.shell.ShellAgent - RUNNING

simulator: org.arl.unet.sim.SimulationAgent - IDLE

phy: org.arl.unet.sim.HalfDuplexModem - IDLE

bbmon: org.arl.unet.bb.BasebandSignalMonitor - IDLE

arp: org.arl.unet.addr.AddressResolution - IDLE

transport: org.arl.unet.transport.SWTransport - IDLE

echo: EchoDaemon - IDLE (2)

router: org.arl.unet.net.Router - IDLE

mac: org.arl.unet.mac.CSMA - IDLE

WebGW-5c9c1c68385a388f: REMOTE| 1 |

Create an agent called

echo

based on the

EchoDaemon

class.

|

| 2 |

We see that the

echo

agent is now running.

|

Our daemon is up and running!

Once the daemon is successfully loaded on node B, we can test it from node A:

> subscribe phy (1)

> phy << new DatagramReq(to: host('B'), protocol: Protocol.USER, data: [42]) (2)

AGREE

phy >> TxFrameNtf:INFORM[type:DATA txTime:2809812247]

phy >> RxFrameStartNtf:INFORM[type:DATA rxTime:2811767943]

phy >> RxFrameNtf:INFORM[type:DATA from:31 to:232 rxTime:2811767943 (1 byte)]

> ntf.data

[42] (3)| 1 |

We subscribe to

phy

so that we can see the incoming echo response from the peer node.

|

| 2 | Transmit a physical layer frame containing the echo request and some data. |

| 3 | The data we sent was echoed back. |

We have written our first agent! Was easy, wasn’t it?

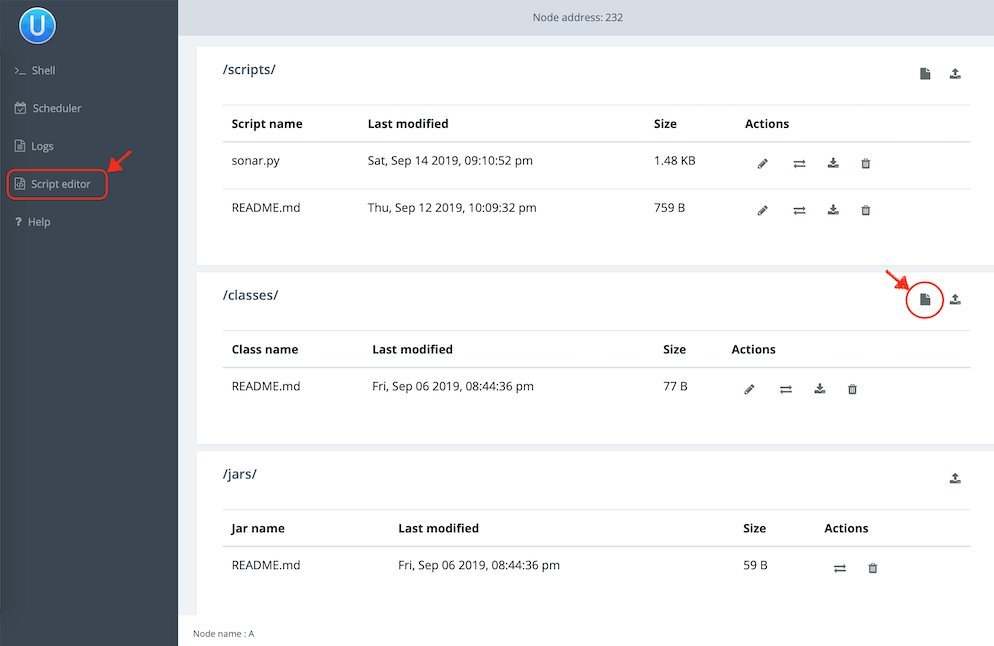

Unet modems also have a

classes

folder that accepts Groovy source files or compiled Java/Groovy class files. You can use the web interface of the modem to upload files to that folder. If your code has many class files, you may wish to package them together into a jar archive and place it in the

jars

folder.

|

28.3. Java echo daemon

If you’re a Java programmer and find the Groovy syntax daunting, you might prefer to write your agents in pure Java (at the expense of verbosity and more steps for testing). This is the equivalent Java code below for the Groovy agent we developed in the last section:

import org.arl.fjage.*;

import org.arl.unet.*;

public class EchoDaemon extends UnetAgent {

@Override

public void startup() {

// subscribe to all agents that provide the datagram service

subscribeForService(Services.DATAGRAM);

}

@Override

public void processMessage(Message msg) {

if (msg instanceof DatagramNtf && ((DatagramNtf)msg).getProtocol() == Protocol.USER) {

// we got an echo request!

// respond with a protocol DATA datagram

DatagramNtf ntf = (DatagramNtf)msg;

DatagramReq req = new DatagramReq(ntf.getSender());

req.setTo(ntf.getFrom());

req.setProtocol(Protocol.DATA);

req.setData(ntf.getData());

send(req);

}

}

}

In Java, you’ll first need to compile the Java code. Create a

EchoDaemon.java

file with the above contents. To compile it, you’ll need to have fjåge and unet-framework jar files on the classpath:

$ javac -cp lib/fjage-1.8.0.jar:lib/unet-framework-3.2.0.jar EchoDaemon.java

You should now have a

EchoDaemon.class

file which you copy to the

classes

folder. To avoid duplicate classes, remember to first delete the

EchoDaemon.groovy

file!

Finally, you can run the 2-node network simulator and test the agent, just as you did in the previous section.

28.4. Behaviors

Agents implement most of their functionality with behaviors.

| UnetStack is implemented on top of the fjåge agent framework. fjåge provides a set of standard behaviors for agents to extend. We will explore some of these behaviors in this section, but you are encouraged to read the fjåge documentation at your leisure to learn more. |

We have been implicitly using two behaviors so far. The

startup()

method is called by the

UnetAgent

base class using a

OneShotBehavior

, and the

processMessage()

method is called from a

MessageBehavior

. While you could have manually added these behaviors, the

UnetAgent

base class does this for you, because almost all Unet agents require this.

Let’s next look at a use case for explicitly adding other behaviors. Say we wanted our echo daemon to not respond immediately, but after 7 seconds. How would we do that?

We could of course add a

delay(7000)

in the

processMessage()

method, but that would be a bad idea. If we did that, the agent would sleep for 7 seconds on receiving a request and not process any request from any other nodes! We want the agent to be responsive while waiting, and so do not want to block execution. Instead, we want a behavior that will occur 7 seconds later — this is precisely what a

WakerBehavior

does. Here’s our new

processMessage()

method:

@Override

void processMessage(Message msg) {

if (msg instanceof DatagramNtf && msg.protocol == Protocol.USER) {

// respond to protocol USER datagram with protocol DATA datagram after 7 seconds

add new WakerBehavior(7000, {

send new DatagramReq(

recipient: msg.sender,

to: msg.from,

protocol: Protocol.DATA,

data: msg.data

)

})

}

}

The

WakerBehavior

that we add is triggered 7000 ms later, and the echo response is sent in that behavior. Simple!

Behaviors in Groovy use closures to make the syntax easy to work with. If you were writing your agent in Java, you’d need to create an anonymous class and override the

onWake()

method.

|

Go ahead and replace the

processMessage()

method in your

EchoDaemon.groovy

file and try it! In order to reload the agent, all you need to do on node B is:

> container.kill echo

true

> container.add 'echo', new EchoDaemon();And now you can send an echo request from node A as before and see that the response is delayed by 7 seconds.

You could also send a second request during those 7 seconds, and the echo daemon on node B would process that concurrently. You can send 2 echo requests right after each other, and you’ll see the corresponding echo responses 7 seconds later, but right after each other.

28.5. Parameters

We have seen many agents with parameters that you can get/set. If we wanted to make our echo daemon delay configurable, it would be perfect to expose it as a parameter. Let’s do that next.

With the echo daemon loaded on node B, we see that it doesn’t have any configurable parameters by default:

> echo

<<< EchoDaemon >>>

Let’s add a title, description and one

delay

parameter to our daemon:

import org.arl.fjage.*

import org.arl.fjage.param.Parameter

import org.arl.unet.*

class EchoDaemon extends UnetAgent {

enum Params implements Parameter { (1)

delay

}

final String title = 'Echo Daemon' (2)

final String description = 'Echoes any USER datagrams back as DATA' (3)

int delay = 7000 (4)

@Override

void startup() {

// subscribe to all agents that provide the datagram service

subscribeForService(Services.DATAGRAM)

}

@Override

void processMessage(Message msg) {

if (msg instanceof DatagramNtf && msg.protocol == Protocol.USER) {

// respond to protocol USER datagram with protocol DATA datagram after 7 seconds

add new WakerBehavior(delay, {

send new DatagramReq(

recipient: msg.sender,

to: msg.from,

protocol: Protocol.DATA,

data: msg.data

)

})

}

}

List<Parameter> getParameterList() { (5)

allOf(Params)

}

}| 1 | Declare a list of parameters that the agent advertises. We have declared this enum as an inner class, but you could choose to declare it as a separate class if you wish. |

| 2 | Provide a descriptive title for the agent. |

| 3 | Provide a descriptive text for the agent. |

| 4 | Declare the parameter. |

| 5 | Advertise the list of parameters. |

| Note that we had to take 3 steps to add a parameter: declare a list of parameters, declare the parameter, and advertise the parameter. While this might seem like a lot, bear in mind that parameters are much more than just an agent’s class attributes. Parameters can be get/set remotely, even from a different Java VM, different computer, or through a UnetSocket gateway API. |

If you were writing the agent in Java instead of Groovy, you’d need to implement getters and setters for parameter

delay

, rather than simply declare the attribute. This is because Groovy automatically creates the getters and setters for you.

|

Let’s see how the agent looks with parameters. Reload the agent on node B and check its parameters:

> container.kill agent('echo')

true

> container.add 'echo', new EchoDaemon();

> echo

<<< Echo Daemon >>> (1)

Echoes any USER datagrams back as DATA (2)

[EchoDaemon.Params]

delay = 7000

> echo.delay

7000

> echo.delay = 5000

5000

> echo.delay

5000| 1 | Notice the change in title. |

| 2 | The description is shown here. |

We have changed the delay from 7 seconds to 5 seconds. Go ahead and send a echo request from node A and see that you get a response back in 5 seconds!

If you want to compute parameter values on demand or validate parameters, you can implement getters/setters for the parameter, and they will be called. If you want a read-only parameter, you can declare the attribute as

private

and implement only a getter for that parameter.

|

While our example above uses a static description, the description can also be dynamic. This can be useful if you want to display agent’s status information in the description. To implement dynamic descriptions, simply replace the

description

attribute by a getter

getDescription()

that returns a

String

description when called.

|

28.6. Services, capabilities, and notifications

Most of the agents we have been interacting with, have advertised services, and sometimes, optional capabilities. They also honor requests and publish unsolicited notifications. All of these are quite straightforward to implement, and you can explore some of these features in this blog article on how to implement a simple PHYSICAL service agent (modem driver). We will explore some of these in the next chapter, along with other cool features like finite state machine behaviors and protocol data unit (PDU) codecs.

| <<< [Shell] | [Implementing network protocols] >>> |