6. Routing in larger networks

6.1. MISSION 2013 network

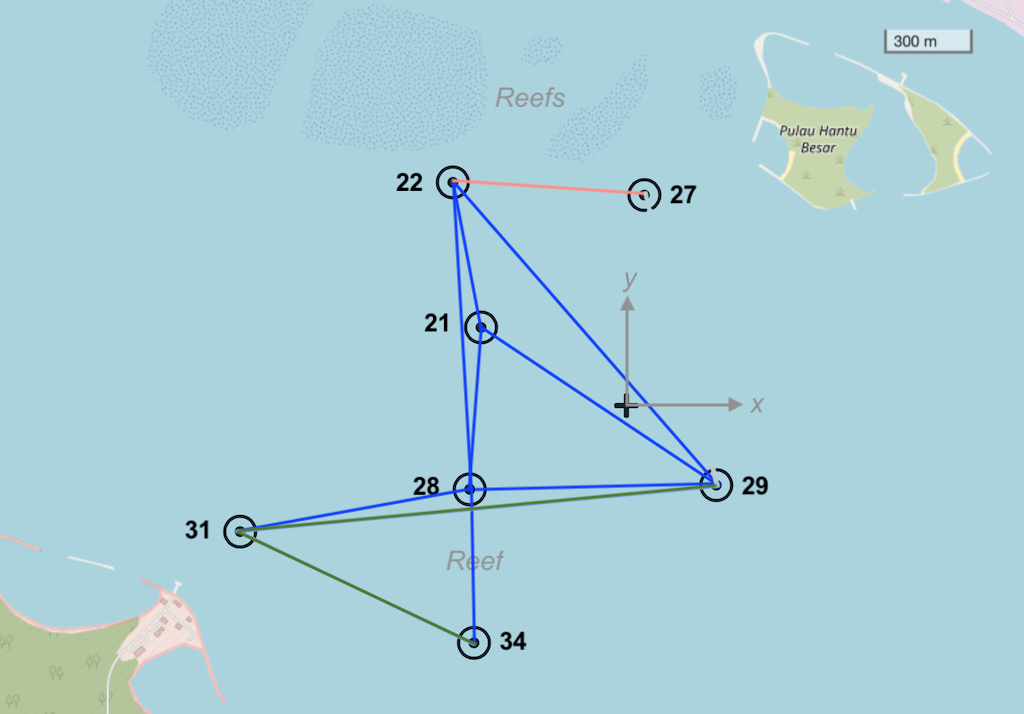

The MISSION 2013 experiment in Singapore featured a 7-node network that was deployed at sea (see

Figure 5

) for several weeks. The network operated in a challenging area with complex 3D bathymetry, several reefs and heavy shipping. During the experiment, we transmitted more than 40000 frames of data and collected statistics on communication performance across various links in the network. These performance statistics are embedded in the

Mission2013a

channel model in UnetStack. We use a simulated version of the MISSION 2013 network to learn how to set up and operate larger networks that require routing.

To start the simulated network, we simply run the

mission2013-network.groovy

simulation script:

$ bin/unet samples/mission2013-network.groovy

MISSION 2013 network

--------------------

Node 21: tcp://localhost:1121, http://localhost:8021/

Node 22: tcp://localhost:1122, http://localhost:8022/

Node 27: tcp://localhost:1127, http://localhost:8027/

Node 28: tcp://localhost:1128, http://localhost:8028/

Node 29: tcp://localhost:1129, http://localhost:8029/

Node 31: tcp://localhost:1131, http://localhost:8031/

Node 34: tcp://localhost:1134, http://localhost:8034/While the MISSION 2013 network is not physically very large (only about 1.5 km across), the challenging environment kept the network from being fully connected, i.e., not all nodes could directly communicate with all others. The average frame delivery ratio (number of successfully delivered frames / number of transmitted frames) on each link is shown in Table 2 . The link quality is also shown on the map in Figure 5 , with dark blue links being the good ones, dark green ones being the weak ones, and brownish one being the very poor link.

| To: From: | 21 | 22 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 31 | 34 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

21 |

- |

0.926 |

0.266 |

0.917 |

0.912 |

0.000 |

0.552 |

|

22 |

0.867 |

- |

0.471 |

0.751 |

0.850 |

0.000 |

0.288 |

|

27 |

0.359 |

0.381 |

- |

0.313 |

0.322 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

|

28 |

0.847 |

0.869 |

0.390 |

- |

0.845 |

0.925 |

0.863 |

|

29 |

0.539 |

0.693 |

0.333 |

0.688 |

- |

0.374 |

0.000 |

|

31 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.902 |

0.805 |

- |

0.795 |

|

34 |

0.236 |

0.436 |

0.000 |

0.684 |

0.000 |

0.544 |

- |

6.2. Connectivity without routing

During the MISSION 2013 experiment, node 21 was a gateway node with surface expression and connectivity to the Internet (via a 3G cellular network). All other nodes were on the seabed and not directly accessible. So let us start by exploring the connectivity from node 21 to other nodes:

Node 21

> ping 22

PING 22

Response from 22: seq=0 rthops=2 time=2892 ms

Response from 22: seq=1 rthops=2 time=2912 ms

Response from 22: seq=2 rthops=2 time=3143 ms

3 packets transmitted, 3 packets received, 0% packet loss

> ping 27

PING 27

Request timeout for seq 0

Request timeout for seq 1

Response from 27: seq=2 rthops=2 time=11075 ms

3 packets transmitted, 1 packets received, 67% packet loss

> ping 28

PING 28

Response from 28: seq=0 rthops=2 time=2952 ms

Response from 28: seq=1 rthops=2 time=3110 ms

Response from 28: seq=2 rthops=2 time=3031 ms

3 packets transmitted, 3 packets received, 0% packet loss

> ping 29

PING 29

Response from 29: seq=0 rthops=2 time=3355 ms

Response from 29: seq=1 rthops=2 time=18720 ms

Request timeout for seq 2

3 packets transmitted, 2 packets received, 33% packet loss

> ping 31

PING 31

Request timeout for seq 0

Request timeout for seq 1

Request timeout for seq 2

3 packets transmitted, 0 packets received, 100% packet loss

> ping 34

PING 34

Request timeout for seq 0

Response from 34: seq=1 rthops=2 time=3294 ms

Response from 34: seq=2 rthops=2 time=3434 ms

3 packets transmitted, 2 packets received, 33% packet lossWe see that the connectivity to nodes 22 and 28 is good, that to nodes 27, 29 and 34 is poorer, and to node 31 is non-existent. Since the simulation is probabilistic, your exact results may differ.

6.3. Static routing

From Figure 5 and Table 2 , we see that node 28 has good connectivity to nodes 31 and 34, so perhaps we could relay datagrams via node 28. Although the link between 22 and 27 seems to be better than the rest, the connectivity to that node is generally poor. Let us set up the following routes:

-

Relay data between nodes 21 and 31 via node 28

-

Relay data between nodes 21 and 34 via node 28

On node 21, we add routes to nodes 31 and 34:

Node 21

> addroute 31, 28

OK

> addroute 34, 28

OK

> routes

uuid to nextHop link reliability hops metric enabled

---------------------------------------------------------------------

riddcc 31 28 uwlink true 0 0.0 true

fkxbqm 34 28 uwlink true 0 0.0 trueOn nodes 31 and 34, we add routes to node 21 via node 28, and enable remote access:

Node 31

> addroute 21, 28

OK

> routes

uuid to nextHop link reliability hops metric enabled

---------------------------------------------------------------------

b7m7w9 21 28 uwlink true 0 0.0 true

> remote.enable = true

true

Node 34

> addroute 21, 28

OK

> routes

uuid to nextHop link reliability hops metric enabled

---------------------------------------------------------------------

s6pjtb 21 28 uwlink true 0 0.0 true

> remote.enable = true

trueNow, we can check out connectivity from node 21 to nodes 31 and 34 again:

Node 21

> ping 31

PING 31

Response from 31: seq=0 rthops=4 time=18930 ms

Response from 31: seq=1 rthops=4 time=10680 ms

Response from 31: seq=2 rthops=4 time=46139 ms

3 packets transmitted, 3 packets received, 0% packet loss

> ping 34

PING 34

Response from 34: seq=0 rthops=4 time=26760 ms

Response from 34: seq=1 rthops=4 time=34408 ms

Response from 34: seq=2 rthops=4 time=21660 ms

3 packets transmitted, 3 packets received, 0% packet lossMuch better!

The pings to nodes 31 and 34 show

rthops

(round trip hops) to be 4, which makes sense, since we have 2-hop routes in each direction. We can ask the routing agent for a trace to check what route the datagram took:

Node 21

> trace 31

[21, 28, 31, 28, 21]This shows that the datagram originated at node 21, passed through node 28 before reaching node 31. Then on the way back, it passed through node 28 again, and reached us back at node 21.

Let us next try to do something using the routes we created. We can get node 21 to ask node 31 to measure the range to node 34 and report it to us. This request will be relayed via node 28, since our routing tables are set up to do so. Remember to set

remote.enable = true

on node 31 before making the request from node 21:

Node 21

> rsh 31, '?range 34'

AGREE

[31]: 873.67As you can see from Table 2 , the connectivity between nodes 31 and 34 is poor in this simulated network. You may need to try this command several times before you get a range estimate. When the ranging fails, you should see the message "ERROR: No response from remote node" back from node 31, which by itself demonstrates successful routing.

If you don’t have the patience to try a few times for range from node 31 to node 34, try getting a range from node 31 to 28, which will be much quicker:

rsh 31, '?range 28'

.

|

6.4. Route discovery

In the previous section, we learned how to set up static routes manually. But what if we are too lazy to determine the routes manually? Or if we don’t have access to the nodes on the seabed to set up routes? We can use the route discovery agent to populate the routing tables.

To see how to do this, let us restart our MISSION 2013 simulation so that the routing tables are empty (alternatively we can remove the routes we created earlier by typing

delroutes

on nodes 21, 31 and 34). We can verify that the routing table is indeed empty:

Node 21

> routes

No routes availableNow, start a route discovery to node 31:

Node 21

> rreq 31

OKPatiently wait for a minute or two before checking the routing table on node 21:

Node 21

> routes

uuid to nextHop link reliability hops metric enabled

---------------------------------------------------------------------

69gnxp 22 22 uwlink true 1 0.0 true

ib3goj 28 28 uwlink true 1 0.0 true

68ozs5 29 29 uwlink true 1 0.0 true

gkfin2 31 29 uwlink true 2 -1.0 trueYour routing table may differ, as the route discovery process is probabilistic. We see that we now have a route to node 31 via node 29. Let us check the routing table on node 31 as well, to see if it has a corresponding entry for a route to node 21:

Node 31

> routes

uuid to nextHop link reliability hops metric enabled

---------------------------------------------------------------------

1hveg6 28 28 uwlink true 1 0.0 true

pjfhin 21 28 uwlink true 3 -1.0 true

n5eqll 34 34 uwlink true 1 0.0 true

8jlzj3 21 34 uwlink true 3 -2.0 true

f6dit 29 29 uwlink true 1 0.0 true

qqtwvd 21 29 uwlink true 3 -2.0 trueIndeed it does! In fact, it has 3 routes back to node 21, one via node 29, and two more via nodes 28 and 34. Of these routes, the route via node 28 has the largest metric, and so will be the route that is used. We can verify that by issuing a trace from node 21:

Node 21

> trace 31

[21, 29, 31, 28, 21]

Since the route discovery process is probabilistic, it may be useful to repeat the route discovery if good routes are not established after a single try. The

rreq

command can also be called with parameters to control the repetition. For example

rreq 31, 3, 6, 30

will initiate 6 route discoveries to node 31 looking for up to 3-hop routes spaced by 30 seconds between discoveries.

|

| <<< [Setting up small networks] | [Wired and over-the-air links] >>> |